Following the traces of Dr. Jean Hissette

An exciting investigation about the life and work of the discoverer

of river blindness

by Guido Kluxen

During my early work as an ophthalmologist I had become interested in the character of my colleague Jean Hissette. On one hand my interest was due to the fact Hissette was the first to discover people with river blindness in Africa around 1930, it was not only a few people he found but thousands straight away. On the other hand I was intrigued by the questions his discovery had amounted to: Why were they found so extraordinarily late? Did river blindness just suddenly occur in thousands of people? No one had seen these river blind people before. What was the reason for the sudden appearance?

Whilst preparing a short article outlining the early stages of tropical ophthalmology of the 19th century, I noticed that river blindness in Africa was only mentioned in 1930 by Jean Hissette. In 1900 there had definitely been no reports of the river blindness. Back then, although aware of the fact, I was unable to explain why it had not been found earlier. For this reason I did not raise the question in my article (Kluxen 1980). Only later on in the 1980s I found an explanation when I saw for myself the anguish of the river blind people in Central Africa. Some of the old tropical doctors could have indeed overseen river blindness, but the main reason is of a different nature. In the time before 1930 African onchocerciasis occurred only very localised with symptomatic ocular complications, verifiable around the Uéle. The reason would have been that the severity of the disease back then varied between different centres of infection and/or individuals only showed minor microfilariae infestation, because tribes used to leave the rivers along which they became ill. Additionally life expectancy used to be much lower and manifestation of ocular affections only occurs late in life long after the initial infection.

The beginning of my investigative efforts

While lecturing ophthalmology in Dusseldorf I distributed a flyer announcing a vacant PhD position tracing Jean Hissette’s background in Belgium. Alfons Labisch, Professor for Medical History, predicted that no one would show an interest in the project. Unfortunately he was correct, although I did find it was as interesting a topic as I had believed. I had no choice but to start investigations myself or I would never find any information about Jean Hissette.

In the meantime, admittedly 18 years had passed since I first raised interest; there had never been time to follow up on accessories of seemingly minor importance within the field of one’s speciality. I wrote to the Central African Museum in Tervuren, Belgium and inquired if Dr. Jean Hissette was a known man there. I was referred to renowned Belgian tropical surgeons, the professors and emeriti, P.G. Janssens and J.P. Vuylsteke, Antwerp, and M. Kivits and M. Lechat, Leuven. I corresponded eagerly with these colleagues, some had already published about Hissette (Henry, Maertens, Janssens 1992). Kivits gave me the address of Hissette’s second daughter Marguerite Ramboux-Hissette, who lived as a widow in her house at the Forêt Soignes in the South of Brussels. Towards the end of 1998 I arranged to meet her. When I arrived Hissette’s third daughter, Marie-Thérèse Delbar-Hissette and one of Marguerite’s daughters were also present. Marguerite showed me photos of her father during his time in the Congo. She also had a few special prints of his publications in scientific journals. I had been prepared enough to be able to take high quality copies of everything in the house on that visit. Out of all of Hissette’s children the oldest daughter Madeleine Feuillat-Hissette was also still alive and resided in Brussels, but due to poor health she was not prepared to meet me. The two youngest children, who left for the Congo in 1929 with their parents Jean and Hilda Hissette (while the three older ones initially stayed in boarding schools in Belgium), had already passed away.

A challenging search for film material

Using the initial information from 1998 I prepared a few shorter papers (Kluxen 1999, Kluxen 2000, Kluxen 2002, Kluxen 2004) and one more detailed paper (Kluxen 2005) about Jean Hissette. In Lacuisine, a district of Florenville-sur-Semois, I found the Hissette-Wouters-de Vriendt family grave in the local cemetery. On the banks of the Semois I also located the former property “la Fresnaye” with the chapel which Hissette’s mother had ordered to be constructed to remind of the events of WWI. Another major discovery followed soon.

In Richard Pearson Strong’s key work, which derived from the results of the Harvard African Expedition of 1934, I found a diminutive note guiding me to my next discovery: “Mr. Mallinckrodt secured excellent photographs and moving pictures of the native inhabitants, the country, and the work of the expedition” (Strong 1938).

This was the only reference to “moving pictures” from the Harvard African Expedition of 1934 that I had heard of. Now I needed to find out where the mentioned movie could be kept. Strong had been the first professor for Tropical Medicines at the Harvard University in Boston and might have left the movie in his institute. I asked my friend and colleague Dr. Dr. Ronald D. Gerste, Gaithersburg, Washington D.C. for help. An inquiry at the medical library of the Harvard University after time proved to be successful. However, initially we were informed that the library exclusively kept books but no movies. After Ronald inquired again, with a little more persistence, a librarian informed us that he found amongst Strong’s books a few canisters labelled “Harvard African Expedition of 1934”. It seemed to be film material but no one knew the content. Hereupon a deposit was paid to send the canisters via registered mail to an institute in New York to be formatted. Then they were returned to Boston and I received a digital copy in form of a US-coded Digital Video. A WDR cameraman accessed the digital copies from the DVCAM for me. I instantly recognised Jean Hissette with the American group. It had truly been worth the investment.

American Scientists check on Hissette’s Observations

Using sequences from the one hour footage of the Harvard movie I prepared a 14 minute long video with English commentary and presented it at the “Ophthalmologica belgica 2004” in Brussels. The Belgian ophthalmologists did not show tremendous interest, but the jury thought it was worth winning a prize.

When I visited Professor Janssens, the retired Director of the Tropical Institute Prince Léopold, Antwerp, in s’Gravenwezel near Antwerp, he confirmed my presumption: The Harvard African Expedition of 1934 had been arranged and paid for by the Belgian colonial administration. This proves that the expedition indeed had been a control commission assigned to check Hissette’s findings on the blind people because they were doubted. Hissette had never mentioned that he was checked. Strong had been urged by the colonial administration to keep silent about the assignment and in 1938 he had hoped to distract from this by writing that the expedition had been entirely his idea. It was feared that the public would have seen the considerable costs of the expedition as a waste since upon their return the Americans confirmed all of Hissette’s published findings about ocular affection through onchocerciasis. By no means had Hissette been displeased with the commission, instead he had felt honoured that such renowned tropical scientists showed an interest in his work. If the colonial administration had trusted Hissette, the commission and the “Harvard African Expedition” would have been dispensable.

A Presentation on Hissette for his Family

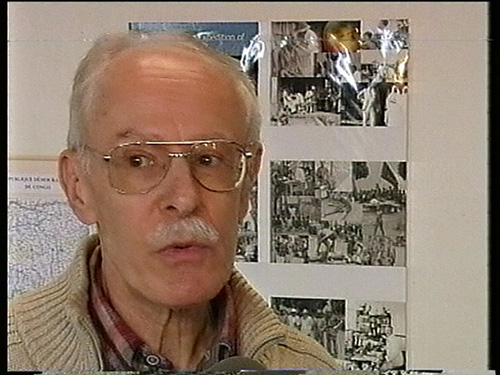

Towards the end of 2004 I received a letter from one of the daughters of Hissette’s youngest and already deceased daughter (Gaby) Rees-Hissette, Cécile Rees-DeJaegher. She was trying to organize a presentation about her grandfather for relatives and some friends at her house in Blanden near Leuven. She wanted me to set a date towards the end of 2004. I chose a Monday night just before Christmas 2004 and expected to get to know a few more relatives to whom I could show the Harvard movie from my lap top. I had thought ahead that if there were a few more people than expected I could repeat the presentation two or three times in groups. Before arriving there I visited Hissette’s grave in Lacuisine and walked alongside the banks of the Semois at “La Fresnaye” and passed the town hall to drop off two copies of my book about the Harvard Expedition (Kluxen 2005). It was getting late but I still managed to arrive just on time. Sixty people had gathered in the large living room awaiting my presentation. I was overwhelmed by this unexpected crowd. The host was a urological head physician, who was accompanied by his younger colleague from his clinic in Brussels, the ophthalmologist Jérôme Vryghem. Fortunately he helped to project the movie onto a big screen. A relative talked briefly about the skin affection caused by onchocerciasis. After my movie they showed an old brief TV production about the life of Belgians in the Congo during colonial times including an interview with Madeleine Feuillat-Hissette, Hissette’s oldest daughter, who holds a portrait of her father in her hands. Outside in the cold, oysters were prepared on the garden stone table and then brought inside the villa for the guests to eat. Marie-Thérèse Delbar-Hissette had come too, but Madeleine had not. Unfortunately Marguerite had passed away since our last meeting. I asked Cécile Rees-DeJaegher if it would be possible to eventually visit Madeleine Feuillat-Hissette, Hissettes oldest daughter. Cécile told me it would be difficult.

The Hissette – Hizette Family Clan

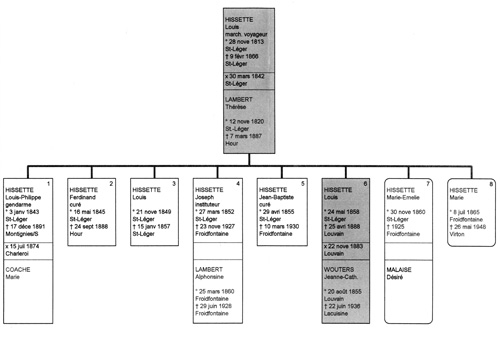

Florenville’s mayoress had forwarded one of the copies of my Harvard African Expedition of 1934 book (Kluxen 2005) that I had left with her to the in Florenville residing Edouard Hizette. Over time he turned out to be a truly reliable friend. He was just like Hissette, a descendent of the famous Hissette-Hizette Family Clan from Virton, but the degree of their relationship remained unknown because it obviously reached far back into the middle ages. Before Edouard learned about my investigations he knew Jean Hissette’s family tree starting with his grandfather (Figure 1). Edouard had a copy of an article that Jean Hissette’s brother, Louis-Ferdinand Hissette (1968), had written about the family tree of iron founders, locksmiths, and mechanics of the d’Orval Abbey near Florenville. When the smithery was destroyed during the French Revolution the two Hisette brothers, who had learnt their trade there, left the abbey. One of them left to Metz, the other one to Gent.

Fig. 1 a: Family tree of Jean Hissette’s grandfather with father Louis Hissette

Fig. 1 b: Jean Hissettes family tree including his siblings

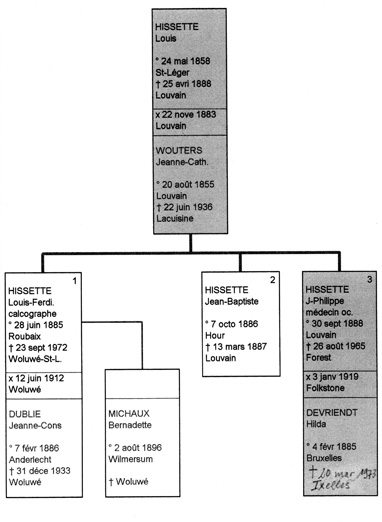

A Hissette exhibition in Florenville

As part of the “Cercle archéologique et historique de la région de Florenville” function Edouard Hizette and I organized in October 2005 a small exhibition about Dr. Jean Hissette from Florenville being the son of the city, the general practitioner and obstetrician. Hissette used to practice here from 1919 until 1929 before he moved into the Congo. The function was open for one week and started with a presentation which many of Florenville’s townspeople came to see. Edourd Hizette gave a presentation to every class of the “école secondaire Sainte-Anne” school where he used to teach Dutch and English (Figure 2). The Belgian TV channel TV Lux produced a short documentary on it for the local news. By courtesy of TV Lux I was allowed to use this short sequence in my new DVD-movie “Dr. Jean Hissette’s Research Expeditions to Elucidate River Blindness” (2011).

Fig. 2: Edouard Hizette during an exhibition on Jean Hissette in Florenville 2005,

frame taken from a TV documentary from TV Lux

On the evening of my presentation of the “Harvard African Expedition” movie many people were present that knew Jean Hissette from their childhood as the town’s family doctor. Comments were given like “He treated me once as a child” or “He assisted in my birth” or “We used to play with his children”. Someone even brought the paper copy of an old picture of Hissette’s clinic in Rue d’Orval No.7 (Figure 3).

Fig. 3: Main square in Florenville. The house located furthest away is the house where Jean Hissette used to work as a physisian, Rue d’Orval Nr. 7.

More material from the daughter and granddaughter

In the following year I received a letter from Cécile Rees-DeJaegher detailing that a meeting with her aunty Madeleine Feuillat, Hissette’s oldest daughter, would now be possible. She was willing to see me.

We left Blanden in the evening for Brussels to meet Madeleine (Figure 4). When we arrived she had a few photo boxes and her father’s letters arranged on the table and looked through them with us. The collection was so extensive I was only able, with her permission, to copy the most important pieces. Madeleine reported that there were even more documents in her basement, but it was too difficult to carry them up into her apartment. These items seemed to be inaccessible at this stage and I feared they might be lost forever. Two years later Madeleine had to abandon her apartment to move into an old people’s home near her daughter Anne in Lillois.

Fig. 4: Madeleine Feuillat-Hissette (at the back) with Gabriele Kluxen, Brussels 2006.

On the table are documents belonging to her father, Jean Hissette.

From Cécile I obtained Anne Dossin-Feuillat’s email address and then arranged with Anne to meet her in her home in Lillois as well as to visit her mother Madeleine in Braine L’Alleud. Both places where situated south of Brussels. I had prepared my lap top beforehand to be able to use my scanner to copy, as fast as possible, the material that would have emerged from Madeleine’s apartment. When I arrived in the house in Lillois in July 2008 the table was covered with books, cardboard boxes, albums, a wooden box with celluloid single-frame-picture films, Hissette’s documents, basically the content of an entire tropical box, as well as a VHS-tape. The latter one contained an analogue copy of Jean Hissette’s original movie, which was recorded from around 1935 onwards with a hand wound camera. The Belgian Television had considered this movie to be lost. The original had in fact gone missing but not the copy which the family had requested from the TV channel.

Anne Dossin-Feuillat and her husband had known me for only three minutes before they told me that I could have everything on the table except for Jean Hissette’s military pass, identification tag and his WWI diary, which I was allowed to have a look at though. It revealed that Hissette had had an affair with a Miss Gaskoye (Figure 5). All the newly gained material now forms the main component of the Hissette-Archive c/o G. Kluxen.

Fig. 5: Jean Hissette around 1916 as a soldier; from a personal album which is in possession of Marie-Thérèse Delbar-Hissette

The summarised facts of the individuals in the discovery story are as follows:

Hissette, Jean (1888-1965)

Vriendt, Hilda de (1885-1973), wife

Hissette, Louis-Ferdinand (1885-1972), brother

Madeleine, daughter (*1920)

Marguerite, daughter (1922-2002)

Marie Thérèse (*1923), called Mimi, daughter

Gabrielle (1925-1983), called Gaby, daughter

George (1926-1988), son (childless)

Hissette-Archive c/o G. Kluxen

The Hissette-Archive comprises of notations, letters, iconographs, photos (glass plates and celluloid), movies, and special prints of his publications, maps, and specialist books from his over 20 years in the Congo. The original material is packed in a metal box, and there are now digital versions of all documents. The archive acts as a source for tropical ophthalmology history projects on river blindness and on Hissette’s work in the Congo. There are still many unknown aspects worth to be investigated. On the basis of his photos and movies it is for example possible to reconstruct the kind of ophthalmological equipment Dr. Jean Hissette had been using in the Congo at certain times (see chapter X in the new book mentioned below). It seems that none of the equipment still exists today.

New Book about Hissette

The new book Dr. Jean Hissette’s Research Expeditions to Elucidate River Blindness (Kaden, Heidelberg 2011) includes an article about the discovery of river blind people, which had been published in a Belgian Scheutists mission journal (Hissette 1932/33). In the new book it is published in English for the very first time (Chapter I). Hissette’s personal notes which were either machine typed or hand written were used to create completely new chapters like: A Journey to Tunisia, through Egypt and Sudan into the Belgian Congo (Chapter III), The Journey from Elisabethville to the Province of Lusambo (Chapter VIII), Anthropophagy of the Kabinda Region (Chapter IX). Also the description of onchocerciasis using Dr. Jean Hissette’s original material (histologies, photos and iconographs) is new, as is the accentuation of his own scientific discoveries. He was the first to discover the Erisipel de la costa in Africa. He also described the scarred chorioretinal fundus before Ridley and discovered that uveitis only develops once microfilariae start dying (Chapter VII). The book includes a DVD, with the same name as the book, which is a new portrayal using Jean Hissette’s personal footage from 1935 onwards and some material of the Harvard African Expedition of 1934, including a short documentary from TV Lux in Florenville from 2005.

Hissette’s cameras

Hissette had two small hand wound cameras; one was relatively heavy from Zeiss Jena with an axial optic for image control. The other was an ultra lightweight AGFA Box with crank handle and image control via an optic through a magnifier viewed from above with the camera held at waist level. The movie material and glass negatives also come from Germany, from Gaevert. On the 19th of July 2008 I was holding both cameras in my hands. Also still existing are Hissette’s photo cameras, from the one in the shape of an accordion for large glass negatives to his modern camera from 1940. They are all kept in the Belgian Lillois near Waterloo.

Ebony-Bar

When leaving the colony in 1952 the Hissettes took, just like many other white people before and after, a heavy three metre long and half metre wide house-bar and some big stools made from dark heavy ebony-wood to Belgium, or at least had arranged the transport. It is a curved rarity carved in with traditional figures of warriors, women with elegant hairstyles and animal patterns. The carving technique was an art used to decorate the clan chief’s throne or palace, but here it was used to create furniture for the European market. This ebony-bar had its spot under the wooden decorations of their house “La Fresnaye” in Lacuisine for a long time. It suited its environment very well. Now it too is in the Belgian Lillois near Waterloo.

Travelling in Hissette’s tracks is currently impossible

So far my investigations have been successful. Within 10 years I had gathered, with some tactical skill and a lot of patience, enough information to report authentically on the character of Jean Hissette. I had even made some friendships along the way. I have to admit now though that these investigations would have been far too comprehensive for the preparation of a medical history dissertation. It probably worked out better to have continued with the preparation of this topic myself whenever I had the time to do so.

I would still like to undertake a journey from Thielen St. Jacques to Luputa and Kabinda, and from there across the Wissmann Mountains to Pania Mutombo and Lusambo and its surroundings to reconstruct where Hissette had found the river blind people and where the Harvard African Expedition of 1934 had operated. However, rivalling militias have been fighting in the area for the past 20 years and it would be irresponsible to undertake this journey before peace is restored in the area.